Matthew’s Memo: An Advocacy Success Story

READ HOW HIS MOTHER AND FORMER TEACHER TURNED MATTHEW’S INITIAL REJECTION INTO AN

ENCOURAGING ADVOCACY SUCCESS STORY. | 5 MIN READ

By Lorene Reagan, MS, RN, Director of Public Relations, IntellectAbility

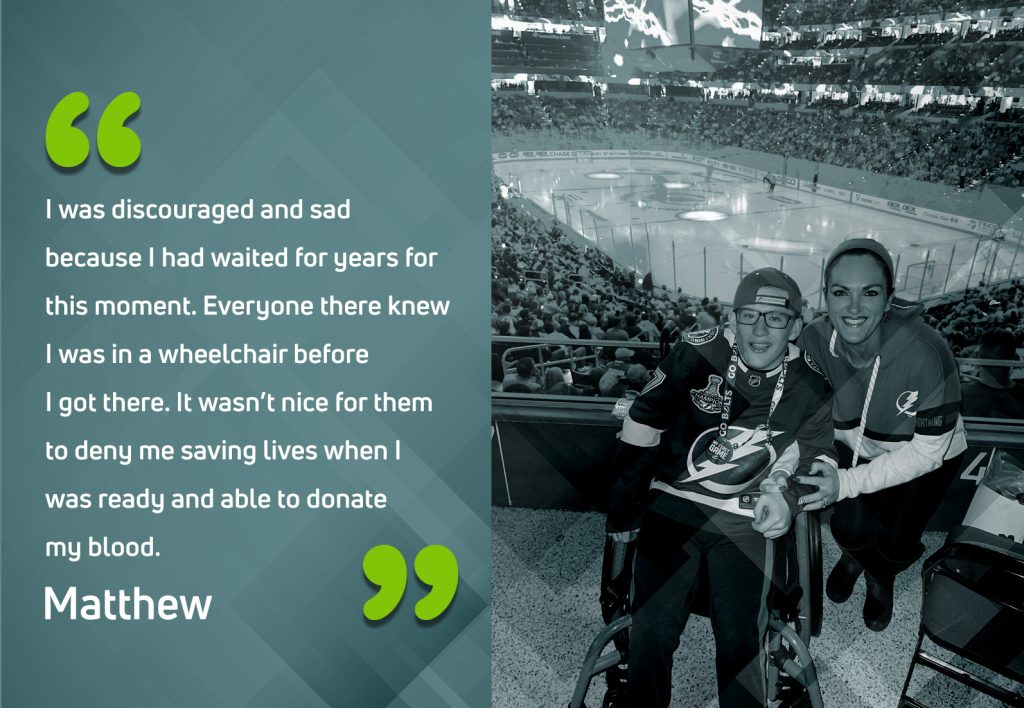

Matthew turned 16 on February 6, 2023. He was excited about this landmark birthday and had made big plans to celebrate by giving blood for the first time. Having accompanied his father, a retired county sheriff, and regular blood donor, many times over the years, he was finally old enough to give blood himself. Plans were made for a celebration at the donor site to commemorate the occasion. As a lifelong Tampa Bay Lightning fan and big-time Victor Hedman fan, Matthew hoped to encourage 77 others to give blood to honor his hockey hero, who wears the #77 jersey.

He arrived at the blood collection center in his community with 20-25 of his supporters and prospective donors on his birthday amid great fanfare and proceeded to the donation room. Shortly after that, he emerged from the room, greatly disappointed because he had been rejected as a blood donor. According to the center, people who can’t independently get up on the donor bed can’t donate. Matthew, who has cerebral palsy, uses a wheelchair and can assist in transfers from the wheelchair to other surfaces but needs a little help to get there. His supporters offered to assist him but were told that the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) requires all donors to be able to get up on the table independently.

Matthew, his mother, and his former teacher and IntellectAbility Inside Sales Representative, Grace Gould, knew this couldn’t be right and asked the staff at the donor site to escalate the situation to leadership within the organization. While others donated, Matthew waited to hear back from the higher-ups. Unfortunately, Matthew was ultimately told he could not donate blood on his birthday because of his inability to access the donor table independently. Matthew, his family, and his supporters decided to make the best of the situation that day and celebrated with cake and balloons.

Matthew’s mother and Grace researched blood donation regulations and requested clarification from the FDA. The Office of Blood Research and Review (OBRR) in the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) provided a prompt response, indicating “there are no specific regulations preventing a person from donating blood due to required assistance in getting on and off a blood donation bed.” Rather, the donor must “be in good health and free from factors that would adversely affect the health of the donor.” The response went on to say, “the collection center is ultimately responsible for determining the eligibility of the donor” and suggested they address their concerns with the center’s medical director.

“I was shocked that in the year 2023, an otherwise healthy individual was denied donating much-needed blood simply because he needed minimal assistance to get up on the donation bed,” said Grace. “What about the organization’s responsibility for complying with the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act)?”

Armed with the FDA’s response, Matthew’s supporters returned to his community collection center, asking for reconsideration. To their credit, the medical directors at the center met to discuss Matthew’s request. They issued a policy memo indicating that people with disabilities can be assisted to get on the donation bed if they bring their own supporters to help them. This communication is referred to as the “Matthew Memo.” And as soon as the mandatory waiting period after being rejected as a donor is up, Matthew plans to be there, front and center, to donate.

We applaud Matthew, his parents, and his supporters for their perseverance. And we encourage you to advocate for health equity for people with disabilities. As we celebrate National Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Disabilities Awareness Month, we recognize and salute the countless direct supporters who work to advocate for and enhance the lives of people with disabilities every day

Attain Person-Centered Thinking skills to positively

advocate and support people with IDD in achieving their goals.

I’m probably leaving out a few, but the idea is to think about all possible causes of pain or discomfort that could be causing a behavior change. Once all medical causes have been ruled out, it’s time to look for other potential reasons, including those from social, environmental, and behavioral perspectives.

I’m probably leaving out a few, but the idea is to think about all possible causes of pain or discomfort that could be causing a behavior change. Once all medical causes have been ruled out, it’s time to look for other potential reasons, including those from social, environmental, and behavioral perspectives.

Health-related Resources for People with IDD and Their Supporters

Health-related Resources for People with IDD and Their Supporters With significant health disparities noted in people with IDD, it is important that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), their supporters, and healthcare providers educate themselves on the different health risks that are more commonly seen in people with IDD and about what can be done to prevent serious complications. Supporters and healthcare providers are often challenged in finding helpful information related to healthcare for people with IDD. As a physician who started practicing in this field in the 1990s, finding clinically relevant information about healthcare for people with IDD was challenging. Fortunately, over the past several years, more resources have been developed that relate specifically to healthcare issues and improving health equity for people with IDD. In this article, you’ll find a listing of websites, tools, and training available to provide information and guidance to you, whether a family member, paid supporter, healthcare provider, or person with IDD.

With significant health disparities noted in people with IDD, it is important that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), their supporters, and healthcare providers educate themselves on the different health risks that are more commonly seen in people with IDD and about what can be done to prevent serious complications. Supporters and healthcare providers are often challenged in finding helpful information related to healthcare for people with IDD. As a physician who started practicing in this field in the 1990s, finding clinically relevant information about healthcare for people with IDD was challenging. Fortunately, over the past several years, more resources have been developed that relate specifically to healthcare issues and improving health equity for people with IDD. In this article, you’ll find a listing of websites, tools, and training available to provide information and guidance to you, whether a family member, paid supporter, healthcare provider, or person with IDD.

Mitchell was taken to the ER because his supporter noted that he was becoming noticeably agitated, was refusing to eat and had begun biting his arm intermittently. His supporter, who knew him well, recalled how he had done this a few times in the past, and most of the time, he was eventually found to have some underlying condition that caused him discomfort. Unfortunately, on some of those previous occasions, it took several clinician visits to get to the right diagnosis.

Mitchell was taken to the ER because his supporter noted that he was becoming noticeably agitated, was refusing to eat and had begun biting his arm intermittently. His supporter, who knew him well, recalled how he had done this a few times in the past, and most of the time, he was eventually found to have some underlying condition that caused him discomfort. Unfortunately, on some of those previous occasions, it took several clinician visits to get to the right diagnosis.

THREE BASIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAINTAINING A COMPETENT AND DIVERSE WORKFORCE | 4 MIN READ

THREE BASIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAINTAINING A COMPETENT AND DIVERSE WORKFORCE | 4 MIN READ