Diagnostic Overshadowing – A Danger to People with IDD

Diagnostic Overshadowing – A Danger to People with IDD

By Craig Escudé, MD, FAAFP, FAADM | November 2022 | 8 Minute Read

As published in Exceptional Parent Magazine, a publication providing practical advice, emotional support, and the most up-to-date educational information for families of children and adults with disabilities and special healthcare needs. We invite you to subscribe by visiting their website.

Mitchell was taken to the ER because his supporter noted that he was becoming noticeably agitated, was refusing to eat and had begun biting his arm intermittently. His supporter, who knew him well, recalled how he had done this a few times in the past, and most of the time, he was eventually found to have some underlying condition that caused him discomfort. Unfortunately, on some of those previous occasions, it took several clinician visits to get to the right diagnosis.

Mitchell was taken to the ER because his supporter noted that he was becoming noticeably agitated, was refusing to eat and had begun biting his arm intermittently. His supporter, who knew him well, recalled how he had done this a few times in the past, and most of the time, he was eventually found to have some underlying condition that caused him discomfort. Unfortunately, on some of those previous occasions, it took several clinician visits to get to the right diagnosis.

Because Mitchell does not use words to communicate, it can be quite challenging for clinicians to determine what might be going on. Once, his supporter recalled, he had a dental abscess that caused the same behavior, and it wasn’t until after going to the ER and having multiple tests done, seeing a primary care physician and a psychiatrist due to his self-abusive behavior, and being started on 2 different behavioral medications, that an astute nurse who had experience in the IDD field insisted on a dental exam. Once his dental abscess was treated properly, he returned to his usual, pleasant self, and his behavior medications were discontinued.

Diagnostic Overshadowing

When a person’s symptoms or behavior are attributed to their disability without looking for treatable underlying medical causes, it is called “diagnostic overshadowing,” which was the recent focus of a Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert released in June of 2022. In it, they state that “diagnostic overshadowing contributes to health disparities and is of particular concern in groups experiencing health disparities, such as individuals with disabilities.” In addition, “individuals with disabilities are at greater risk of diagnostic overshadowing” and “the potential of diagnostic overshadowing presents added risk to individuals with disabilities.” I could not agree more with those statements. The Alert goes on to state that “Speed, stress, and lack of training contribute to diagnostic overshadowing.” I believe that of these three, the latter, “lack of training,” is the factor that we can do the most about.

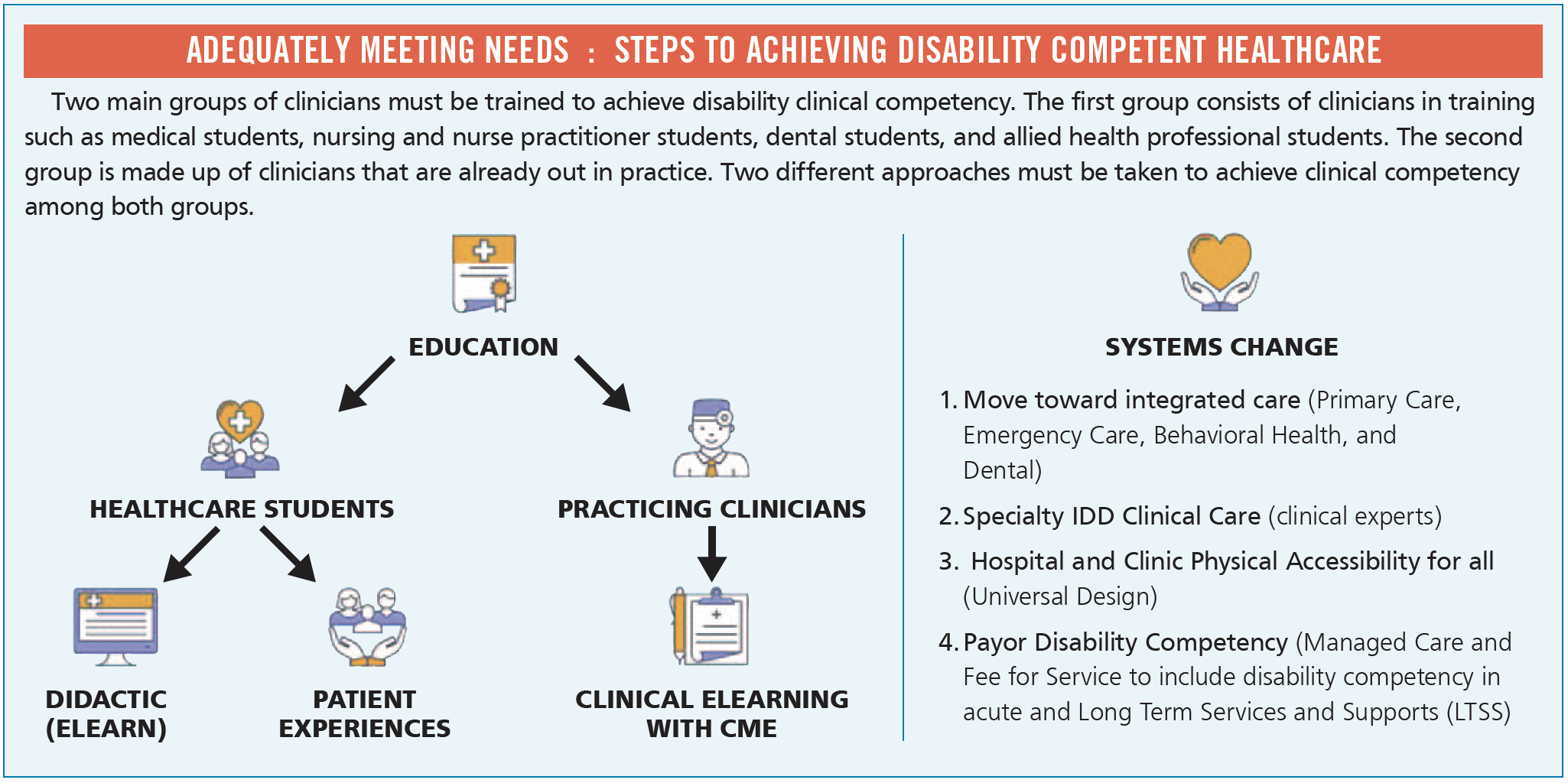

Medical schools and other health professional schools should be required to provide training to students specifically relating to providing healthcare to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). In order to address diagnostic overshadowing, it is essential to educate clinicians about common presentations of treatable medical illness in people with IDD, medication management, and The Fatal Five, which are the top causes of preventable morbidity and mortality in people with IDD. The Fatal Five includes aspiration, constipation, dehydration, seizures, and sepsis with the addition of gastroesophageal reflux. In addition, education on physical and nutritional supports which relates to physical and nutritional measures to facilitate safety in eating and bowel elimination, co-occurring mental illness, vitamin D deficiency, differences in dementia presentations, and other clinical topics, are vital to improving health and wellness for people with IDD.

You may notice that the topics I listed go beyond what one might call “disability competency” and involve specific medical conditions. While learning about making healthcare facilities more physically accessible, creating calm environments for people with sensory differences, and learning how to best communicate with people with disabilities and their supporters are extremely important, there are actual, specific clinical evaluation and diagnostic skills and concepts that healthcare professionals should be taught. And the responsibility lies with health professional schools, medical societies, and licensing and regulatory bodies to ensure these skills are taught to students and clinicians already in practice so the estimated 10 to 16 million people in the US with IDD can count on them to reduce health inequities, avoid preventable illness and death, and eliminate unnecessary suffering from unmet healthcare needs.

Let’s get back to Mitchell.

At the emergency room, Mitchell and his supporter met Sarah, a nurse who received her degree from a school that taught IDD healthcare principles. Sarah spoke with Mitchell directly, in plain language, and asked Mitchell to sit down and demonstrated, one at a time, how she was going to check his blood pressure and other vitals, then escorted Mitchell to a quiet room and notified the physician that Mitchell had an intellectual disability and was ready to be seen. Mitchell then saw Dr. Smith, who had recently completed an online training course provided through his state’s developmental disabilities agency. In that course, Dr. Smith learned about diagnostic overshadowing and the many different ways that people with IDD might express pain and discomfort and the tendency for overuse of psychotropic medications to control behavior. Dr. Smith spoke to both Mitchell and his supporter and asked a number of questions relating to common causes of pain in people with IDD. Dr. Smith learned that Mitchell seemed to become more aggressive around mealtimes and refused to eat. He was also waking up at night yelling for no apparent reason while curling up into a fetal position. Dr. Smith then evaluated Mitchell for gastrointestinal issues. He found that Mitchell had severe constipation which is one of the most common preventable causes of illness in people with IDD. Dr. Smith provided prompt treatment, and upon discharge, Dr. Smith recommended additional fiber and fluids and to follow up with his regular doctor if the symptoms were not better within 24-48 hours.

Mitchell went back to his home, and the next day, he was back to his usual self. Both Mitchell and his supporter were so pleased that the healthcare staff treated them respectfully, listened to Mitchell’s story, and had specific training about the healthcare needs of people with IDD. When health professional schools implement this vital training, better health and lower rates of unnecessary suffering for people with IDD will surely follow.

THREE BASIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAINTAINING A COMPETENT AND DIVERSE WORKFORCE | 4 MIN READ

THREE BASIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAINTAINING A COMPETENT AND DIVERSE WORKFORCE | 4 MIN READ

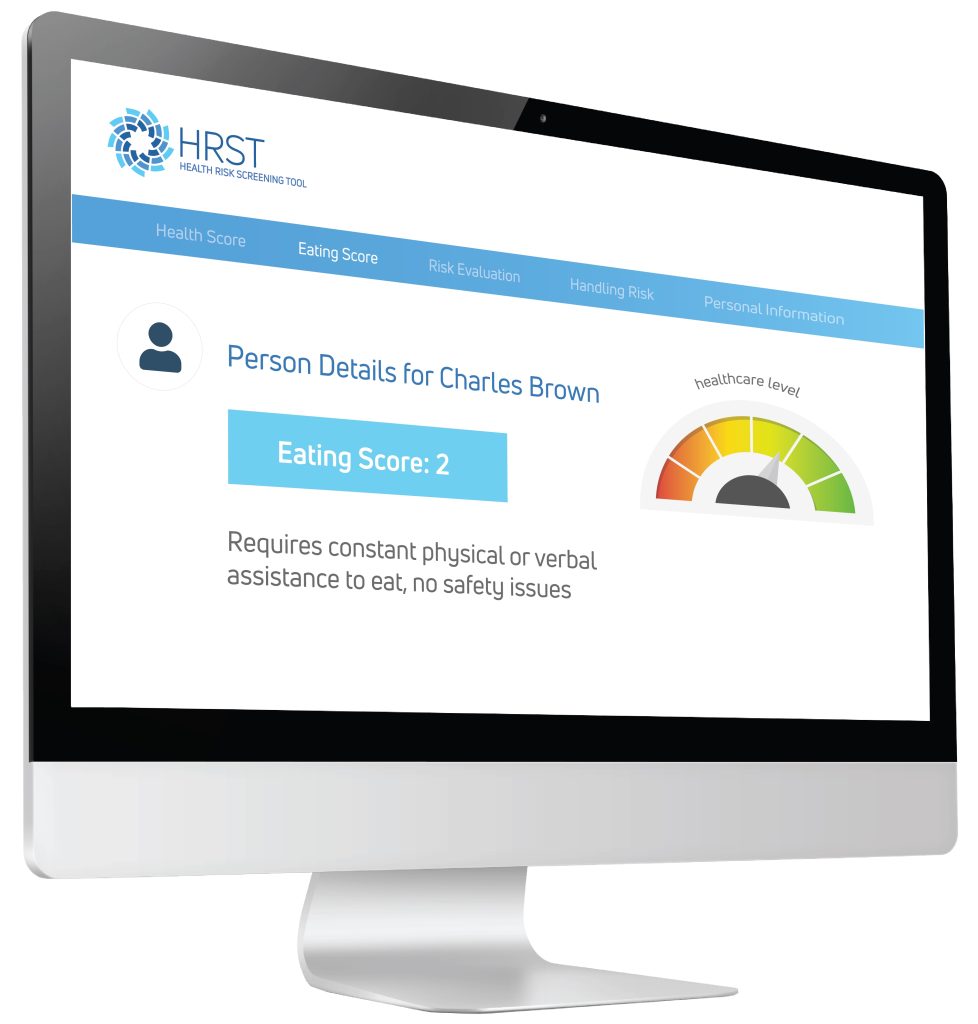

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of

The

The